A world of whistling frogs...

Text & Photographs Linda de Jager

From the Winter 2022 issue

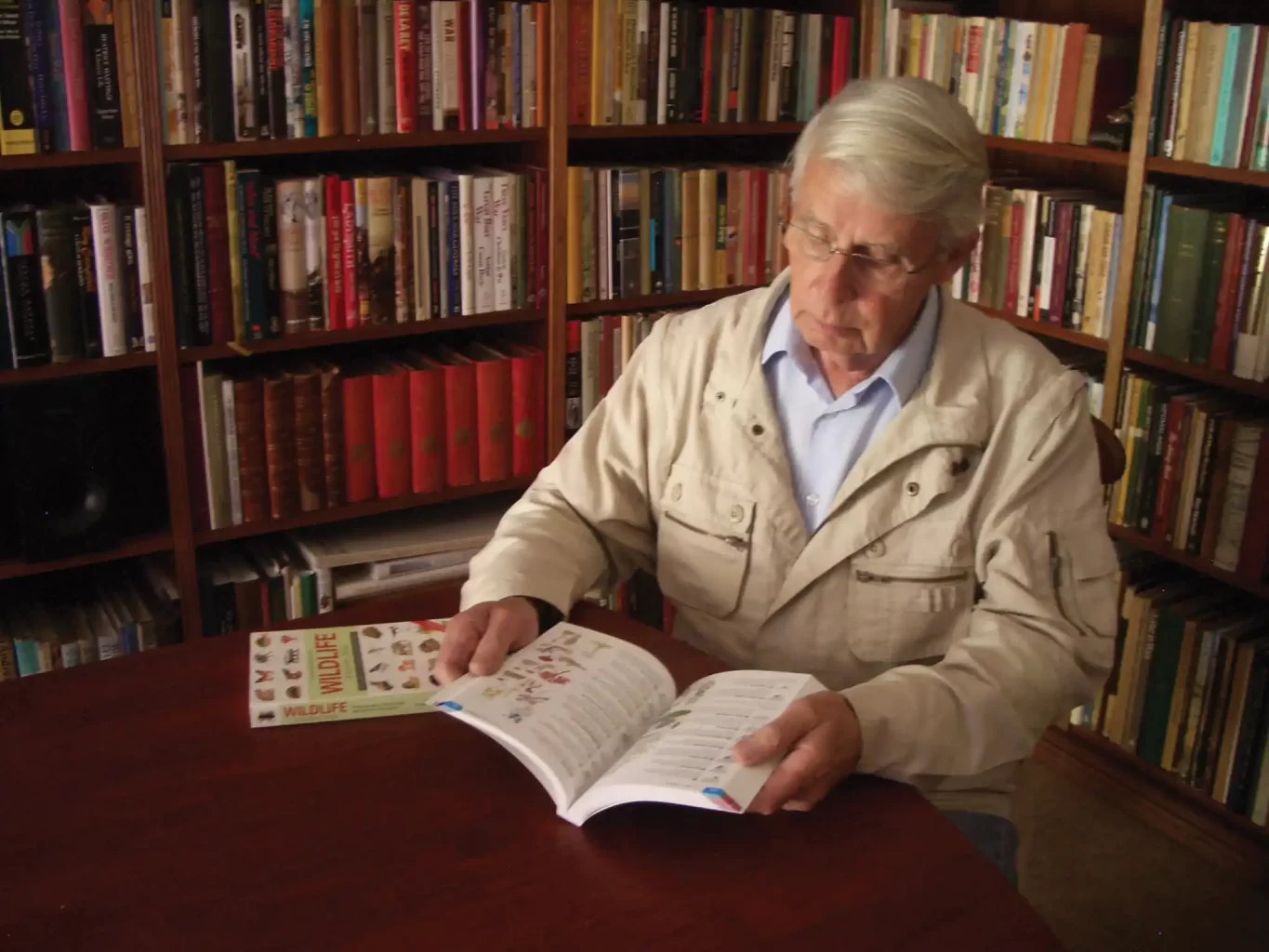

Not many people can claim that a rain frog was named after them – even fewer can assert that they were once almost arrested for searching for one – in a desert of all places. Let me introduce you to the world of frog expert Vincent Carruthers. He is a well-known contributor to amphibian research and co-authored several books: when you hear a long, drawn-out rising whistle in the Namib Desert and it seems to be coming from nowhere, you may want to look again and search for a small creature (about two inches in size) with bulging eyes.

Some locals refer to the desert rain frog (woestynpadda) as a melkpadda (milk frog) because they exude a milky poison when threatened. The elusive Breviceps macrops frequently makes it to the list of the world’s cutest animals. Not only because of its stuffed animal looks, but also because of the sound it makes when it is handled or disturbed: it squeaks like a plastic toy.

Walking on snow shoes in the sand…

Perhaps because this creature cannot hop or leap away, but has to walk around on the sand, it displays a piercing squeak with its mouth open wide when alarmed. Vincent explains: “Its feet are quite unlike those of any of the other rain frogs which all have unwebbed toes and a massive calloused tubercle on the heel with which they dig backwards into the ground. The desert rain frog has no such tubercle and an extensive fleshy web extends between fingers and toes. This enables it to walk on the loose sand like camels’ padded feet or as if wearing snow shoes.”

Fearing that the desert rain frog was on the brink of extinction, Vincent and a colleague set out to search for it in the late 1970s. They were gathering information for a new book on amphibians.

A wondrous claim and a strange arrest

This frog species is confined to a narrow coastal strip in north-western Namaqualand and southern Namibia. It occurs in the area of the 26 000-square-kilometre Sperrgebiet, proclaimed a national park in 2008. Prior to that the area was strictly guarded and only accessible to diamond prospectors. Today it is limited to small-scale mining. The Orange River is the park’s southernmost border. It seldom rains there. Annual precipitation is about 60 mm and comes mainly in the form of mist that condenses in the inflowing air from the Atlantic. “The frogs call in the mist from exposed positions on the sand or shallow excavations. It is a long, drawn-out rising whistle,” says Vincent. “The desert rain frog was first discovered in 1907 and there were specimens in bottles in a couple of museums in South Africa. They were all labelled Port Nolloth or Alexander Bay, but none were dated later than 1936.” The research team visited Port Nolloth in October 1977. For days on end they were exploring the characteristic burrows – just a conical depression in the sand – searching for the frog’s distinctive footprints leading to it. A quick excavation of the top 10 cm of dry sand might just reveal a dumpy little frog resting at the level where the sand retains moisture from the previous morning mist.

Says Vicent: “Life on the dunes is remarkably active. Tracks of lizards, rodents, beetles and other insects criss-cross the sand between the curious succulent plants. Once or twice we found evidence of a sad story where the tracks of a frog met those of a meerkat at a blood-stained point of intersection. The excitement of our hunt carried on well after dark and we ventured unintentionally close to the line that separates the open desert from the prohibited diamondiferous areas owned by De Beers. All of a sudden the figure of a policeman materialised out of the dark. Polite but clearly suspicious he had been watching our torches flitting about the dunes and noted the obvious fact that we were searching in the sand close to diamondiferous ground – curious behaviour for out-of-town strangers and not difficult to draw the obvious conclusion. Illicit diamond dealing was taken very seriously in those days. We explained that we were looking for frogs. In the desert? Yes. “Frogs”, he explained patiently, “do not occur in deserts”. So we were forced to accompany him to the local police station. Amid disbelieving chuckles, he explained to his police colleagues that we were from Johannesburg (clearly suspect), Wits University (definitely criminals, given the context of the time), and we were looking for, wait for it – frogs! In the sand. “And the one ou (chap) says he’s a professor!”

Vincent recalls that their story was so improbable that in the end the police decided it had to be true. They were allowed to go back to their camp and returned the following day armed with their collecting boxes full of legitimate frogs, and all ended happily.

Still unique and still vulnerable

Vincent is fascinated by the way this species has adapted to desert conditions. He explains that rain frogs are an almost exclusively southern African genus, Breviceps, and many of the 18-odd species are confined to forests or high rainfall regions. “They lay their eggs in damp burrows under the leaf litter on the forest floor. Their tadpoles develop and mature in these burrows and emerge into the leaf litter as fully formed froglets without ever having been near water. That life cycle should only be possible in an extremely moist, shady habitat, yet the desert rain frog has adapted to the exact opposite, an exceptionally arid desert. It survives in this seemingly inhospitable environment by burying itself 10 or 15 centimetres below the surface where the sand retains a certain amount of moisture. It moves about at night, frequently visiting dung heaps to hunt for insects.”

Another special adaptation is the extremely thin and vascular skin on the belly. This allows moisture to be absorbed from the damp sand below the surface.

While most of the mining that threatened their habitat has now stopped, and large areas of ground have been restored, the frogs remain vulnerable. In the SANBI survey of endangered species (Measey, G.J. Ensuring a Future for South Africa’s Frogs – a Strategy for conservation research. 2011) the ‘vulnerable’ status was retained because “Current estimates suggest that there are less than 10,000 individuals and that there has been a decline of 10% within three generations… it is not yet known whether it has returned to restored habitat.”

A remarkable case of parallel evolution

Vincent guards a treasure chest of fascinating information. He explains that there is another closely related species, the Namaqua rain frog, Breviceps namaquensis, that occurs along the Namaqualand coast and adjacent arid mountains as far south as Langebaan. Its call is very different.

“Rain frogs are confined to southern Africa, but there is a completely unrelated Australian frog, the sandhill frog, Arenophryne rotunda, found in the sand dunes of Shark’s Bay, north of Perth, Western Australia. “It is a very similar environment to the Namib and the frog looks much like a rain frog (rotund with short legs.) It has an almost identical method of laying its eggs in moist sand where they develop into fully formed froglets just like rain frogs do.”

In 2017, Vincent’s dedication as herpetologist received a singular honour in zoology: a new species of rain frog was named after him. The frog has been named Breviceps carruthersi, otherwise known as Carruthers’ rain frog or the Phinda rain frog. The subtropical area of the Phinda Game Reserve in Zululand is far removed from the Namib Desert. Exactly how many desert rain frogs remain alive today is uncertain. But if you bother to search for quite some time, a strange little creature will whistle gently at you as if to say, “I have been here all along.”

Fast facts on the rain frog:

Breviceps Merrem, 1820

19 species, 18 in southern Africa

Desert rain frog (woestynpadda is one species)

Conservation Status: Vulnerable

Where do you find it in Namibia: Along the coastal dunes south of Lüderitz.

How do you know it is a rain frog: Very short legs, flat face, rotund body.

When is your best chance of seeing a rain frog: At night or early morning in the mist.

More to explore

Lüderitz Nest Hotel: A New Era of Elegance on Namibia’s Shores