Presentations | 6 & 8 July

July 2, 2015Conservation l Ecology Field Course at Gobabeb

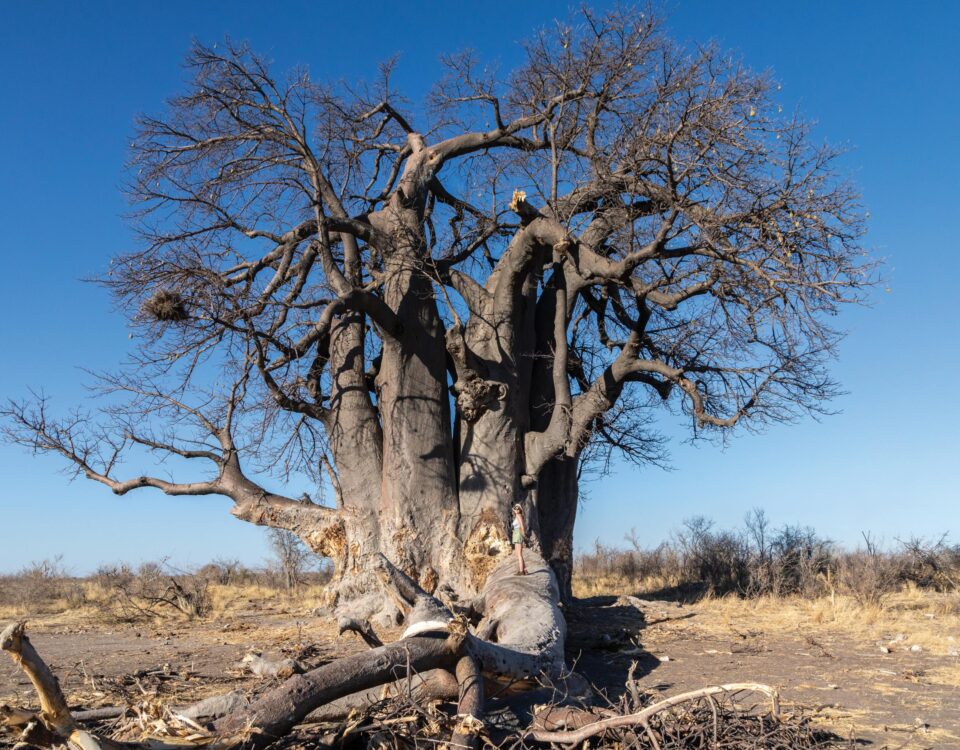

July 7, 2015Standing Tree Abundance, structure and uses of Boabab populations in the Omusati region

University of Namibia

By Faith Munyebvu-Chambara

Considered the largest succulent plant in the world, the baobab tree is steeped in traditional beliefs and uses wherever it occurs in Africa. It can provide food, water, shelter and relief from sickness. If used sustainably, these benefits can be accrued for thousands of years.

The study of indigenous natural resources, including benefits to communities and sustainable management, prompted Faith Munyebvu-Chambara, a Master of Science student from the University of Namibia, to begin a study on the abundance, structure and uses of the baobab.

With funding from the Nedbank Go Green Fund, Faith’s work is centered in two constituencies in the Omusati region, Outapi and Onesi, where significant populations of wild baobabs occur. During the course of her year-long study, the ecological information gained will be useful to monitor any changes to the physical characteristics of the trees and to evaluate the potential to commercialise the sustainable harvesting of their resources. Communities will also gain a greater understanding of the species and its potential for product development, which could ultimately improve the livelihoods of local people.

With a methodical plan, Faith’s research, which is still in its initial phase, is already providing interesting insight into the abundance, uses and attitudes of local people towards this important plant species.

“Currently, most of the people interviewed for my study eat the fruit and throw away the seeds,” reported Faith. “Only a few actually sell the fruits for income. During times of drought such as in 2013, the bark is mainly used to feed cattle and goats.”

Few respondents to the study’s survey reported making use of the tree products to treat ailments, and nothing was mentioned about producing craft items such as mats and baskets out of the baobab fibre. These two facts highlight the scope for adding value to this natural resource in the future.

Culturally, a number of respondents said that the trees’ roots were used to make strings to tie premature babies so that they grow fast and healthy. While from a conservation point of view, given the fact that the historical baobab tree, Ombalantu, is now a heritage centre, the people from the study sites tend to be knowledgeable about the importance of conserving this species.

Faith also reported that “Old people also know about certain baobab trees in which they used to hide during war. They have protected these trees as they carry their history.”

“Interestingly, a number of baobab trees found in towns where new developments are taking place were actually preserved. Areas around the trees are left as open spaces and the fruits of the trees can be accessed by anyone. So, despite some damage being done to some trees’ roots and branches during construction, the species is being preserved even in urban areas.”

From a commercial point of view, Ombalantu Heritage Centre is propagating baobabs and selling them to people, mainly tourists. While baobab fruit pulp is processed and sold as a juice ingredient in Malawi, the potential for sustainable commercial utilization in Namibia is yet to be explored.

As Faith noted, “Considering the smaller baobab populations in Namibia compared to other countries in southern Africa, there is a need to determine how viable it is to commercialise the resource either on a national or international scale, and importantly, to see if and how local communities can benefit from it.”

On its enormous branches and spindly limbs, the baobab tree carries potential to improve human livelihoods if the baobab products are fully but sustainably used in areas where this tree occurs. Clearly, a study to understand the biology of the resource is warranted, and thankfully Faith Munyebvu- Chambara is on the case.

Faith Munyebvu-Chambara

Faith is currently an MSc student at the University of Namibia and an intern at the Namibia Nature Foundation (NNF) where she assists with various conservation projects and organizing stakeholder workshops. Prior to enrolling at UNAM for a collaborative MSc course in Biodiversity Management and Research with Humboldt University, Berlin, Faith worked as a Projects Coordinator with NNF. Faith is in the final stages of finalizing her thesis after having successfully completed a one year course work in 2013. She holds a BSc Hons. in Geography and Environmental Studies from Midlands State University. She has been an associate researcher, coordinator and involved in consultancy work on a number of social and environmental projects in many parts of Namibia such as Torra, Ben Hur, Drimiopsis and Windhoek and in South Sudan. Faith Munyebvu- Chambara continues to pursue her goal of becoming an influential environmentalist to achieve sustainable natural resources management and livelihoods improvement in the region.

Contact

rutendomunyebvu@yahoo.com

Fast Facts

- The African baobab is a deciduous, tropical fruit tree occuring throughout parts of western, north-eastern, central and southern Africa, Oman and Yemen in the Arabian Penisula and Asia

- Occurs locally in sizeable populations in the north-western and in smaller populations in the far north-eastern parts of Namibia

- Reaches heights up to 25 metres and diameters of up to 6-10 metres

- Average life span of 1000-3000 years, although studies have shown that they can reach up to 6000 years

- In Namibia, fruiting normally occurs from November up to May, and harvesting continues until August