CCF – putting research into action and improving the life of Namibians

July 5, 2012Counting wildlife: Namibia one of the greatest biodiversity successes in the world

July 5, 2012By Pauline Lindeque

It is estimated that there were less than 6 000 elephants south of the Zambezi River by 1900, raising fears that they would become extinct in the region. Today this area holds more than 250 000, and the population continues to increase at a rate of approximately 5% per annum. In Angola, Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia elephant numbers have begun to recover over the last decade. In fact, the Southern African countries combined now hold about two thirds of the entire population of African elephant. At current rates of growth, these populations are likely to double in the next 12–15 years.

Within Southern African countries, the adoption and practice of community-based natural resources management (CBNRM) has given elephants and other wildlife economic value. Wildlife management in communal areas surrounding protected areas is now accepted as a land-use option. This has given an opportunity for elephants to expand their range. However, increasing elephant populations coupled with increasing human populations have lead to an increase in negative interactions between the two.

Human/elephant conflict (HEC) is reported in all Southern African countries and is considered one of the biggest difficulties confronting conservation authorities. There are also concerns about the impact of the increasing elephant populations on habitats and biodiversity. A vast majority of these populations are shared. They move across political boundaries, posing inevitable challenges, and are not evenly distributed between the different range states, which offers some opportunities for dispersal.

The Southern African countries have therefore taken the initiative to develop a regional strategy for elephant management and provide a framework for collaboration and harmonisation of elephant management. A meeting to start the process of drafting such a strategy was convened in Victoria Falls from 25–27 May. Over these three days, government representatives from Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe, together with specialists from the African Elephant Specialist Group of the IUCN, the University of Zimbabwe, TRAFFIC and WWF, discussed areas of collaboration and issues that can be addressed at a regional level to enhance the conservation of elephants.

Population

In the past, because of the transboundary nature of many elephant populations, critics have disagreed with the elephant population estimates from Southern Africa, claiming that surveys were not co-ordinated or standardised, and that double counting could have taken place. The region clearly needs to work together to standardise survey techniques and co-ordinate the surveying of transboundary populations.

The region has already identified clusters of transboundary populations that should be surveyed in a synchronised manner (see map), and efforts are underway to achieve this. In some cases, however, lack of resources makes this difficult. The MIKE (Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants) programme has produced a guideline for aerial survey standards that are now generally common practice when surveying savannah elephants. These will form the basis for the standardisation of techniques.

Science and research

Much has been said regarding the impact of elephant populations on the environment and biodiversity. The modification of vegetation from an overabundance of elephants has been well documented and is now a generally accepted phenomenon. However, there are conflicting views on whether these changes are desirable or not; whether they lead to a general loss or increase in biodiversity; and whether they are simply part of a natural cycle. Ecological studies are generally unable to factor in man as an integral component of ecosystems, and it is becoming clear that, if we want elephants to extend beyond the formally protected areas, it is necessary to balance ecological interests and community incentives. Collaboration with regard to studies on elephant movements, as well as studies on the impact of elephants on the environment and other species, will undoubtedly lead to a better basis for planning and management. In particular, maintaining critical corridors for dispersal is an integral part of any regional strategy.

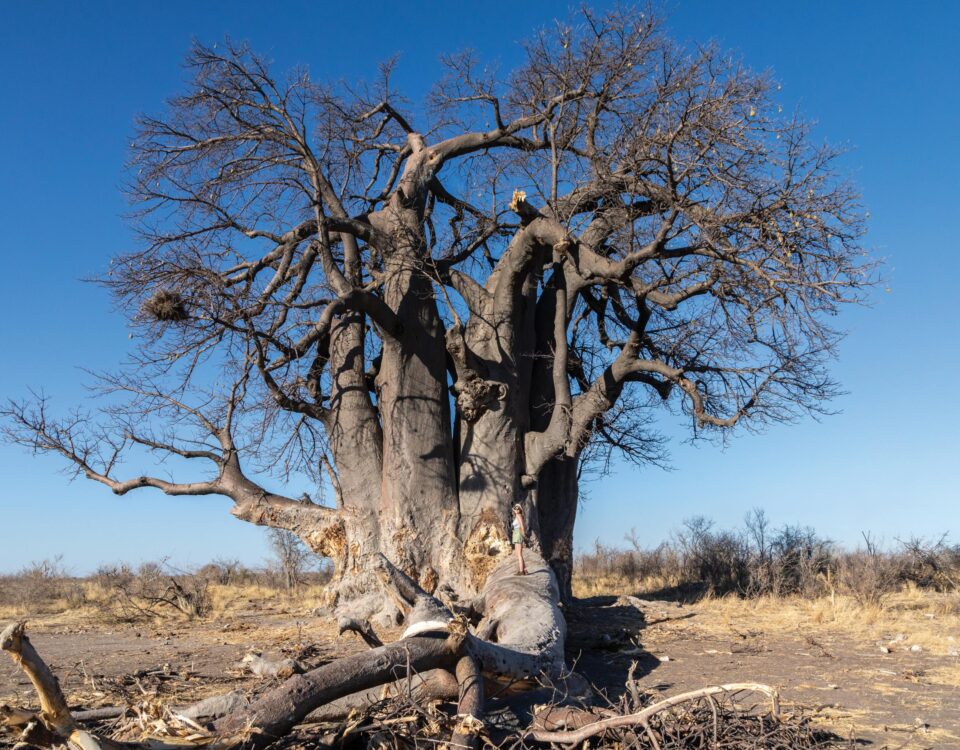

The reality is that there are few if any ‘natural’ ecosystems left (that is systems not impacted in any way by man). At the end of the day management decisions will be taken on value judgments. For example, do we value the presence of baobab trees or are we happy to see them disappear? Values are influenced by cultural, political and economic factors, which might impact negatively or positively on the status of elephant populations and their management at local, national and international levels. In Southern Africa, sustainable use and sustainable development remain a shared philosophy, and the conservation of biodiversity a commitment.

Impact of conflict

In a landscape of widespread poverty and an increasing human population relying on low-performing agricultural systems, it is essential that the social and economic impacts of increasing elephant populations on communities are carefully considered. Impacts are not all necessarily negative, but a careful balance has to be reached to ensure that the elephant population contributes to socioeconomic sustainable development. Namibia’s conservancy programme has been widely recognised as a good model for enhancing community participation in elephant management, and ensuring that benefits return to the communities through sustainable use (both consumptive and non-consumptive).

However, even here it is recognised that individuals often carry the costs, while the benefits go to the communities. In order to understand the full extent of the impact of human-elephant conflict better, it is considered important to standardise the protocols for collecting incidence data as far as possible, in order to allow compilation at a regional level. This will provide the much-needed information to make wise management decisions, and to focus efforts where they are most needed.

Options

The group agreed that there is a range of option interventions that can be considered to deal with elephant management issues, and that no single intervention is likely to be effective on its own. At the same time there is recognition that local situations differ greatly, and that there is no single recipe that will necessarily work for all. Examples of interventions that can be used on their own or in combination include increasing size of conservation areas, translocation, hunting, fencing, manipulating water supplies, contraception, migration corridors, culling and cropping, or even a laissez-faire (do nothing) approach, which is nevertheless a conscious decision that is taken. There was consensus that all management options are legitimate and should be available to countries to draw on appropriately when dealing with specific situations.

Valuable resource

Much of the Southern African approach to elephant conservation depends on elephants becoming an asset rather than a liability to communities. In this respect, there is agreement to continue to collaborate in removing CITES restrictions to trade in order to optimise benefits from elephants. It was also acknowledged that capacity building could take place between the countries to develop techniques and skills to add value to elephant products.

Initiatives

Elephants are a significant tourism attraction. A number of transfrontier conservation initiatives are already in existence or developing in areas of transboundary elephant populations. These initiatives provide an opportunity not only to promote tourism activities, but also to harmonise management approaches in these areas. The ideal is to have an elephant range extending from the west coast to the east coast of Africa.

Southern African countries have agreed to foster appropriate co-ordination at transboundary level in respect of the following issues: land-use planning (conflicting/complementary), mitigation measures, law enforcement, developing trophy quotas and management of trophy hunting and other off-take. It was also agreed that there is good scope for sharing of experiences and lessons learnt, for example regarding mitigation measures to HEC and Community Based Natural Resources Management models. Only by working closely together can the region build on existing successes to the benefit of both elephants and man.

This article appeared in the 2005/6 edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia.