FINDING TREASURE in the middle of nowhere

Text Riéth van Schalkwyk Photographs Roux van Schalkwyk

From the Winter 2022 issue

In the days when we still had our most treasured experiences printed on glossy postcard-size photos, a friend gave me some to remind me of a wondrous experience that I had missed in my travels criss-crossing the country. As you probably know by now, Namibia is a dry country, famous for its deserts and dramatic geographic rock formations, mountains and canyons. Water is a special treat along the 1700-km-long coastline, the perennial rivers on the southern and northern borders and the few big man-made inland dams. Looking at the photos, I squinted to figure out where the captured body of water could be. Not the ocean, because there was a fine line of greyish vegetation visible at the top. The birds were plentiful, but I could not identify a seagull or a cormorant. Definitely not the ocean. In fact, I needed a lot of imagination to fill in the suggestion of expanse inevitably lost with the limitations of a small-format camera. Those photographs with their subtle pastel colours and what were obviously thousands of birds triggered my imagination. For years I had a little flip frame on my desk hosting them, reminding me to go there when the time was ripe.

In Namibia, where drought is a constant reality, the time only came years later – after a long period of drought.

By then, I had heard amazing stories about the Nyae Nyae Pan, like how a lone hippo suddenly appeared one day. Nobody saw it coming, or from where. Travel News correspondent Willie Olivier drove all the way to photograph him, only to find he had left again. Nobody knew where to either. One of the iconic baobab trees, the sentinel on the edge of the pan keeping watch over whoever pitched a tent or rolled out a sleeping bag under it, just crumpled up as these trees do. Again it was Willie who told us, because he found the heap while doing a story on the historic baobabs of Namibia.

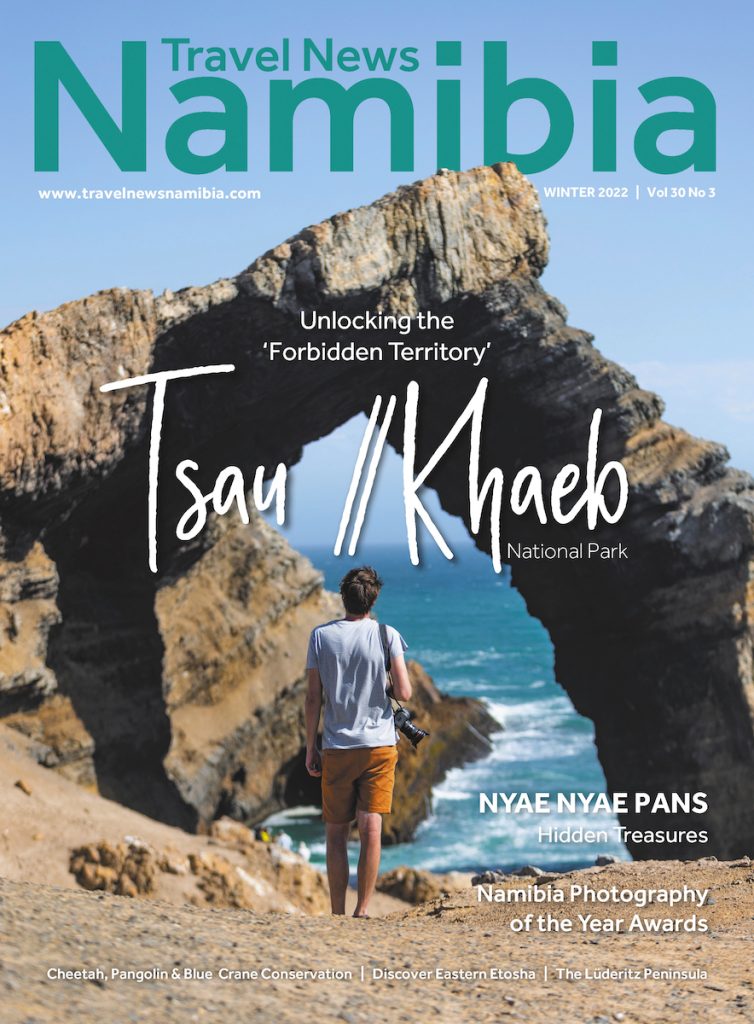

By now the beautiful opening photograph of hundreds of flamingos has given away my story. These thousands of birds on the water in the middle of nowhere are standing in the shallow water of the pan in the Naye Naye Conservancy close to the north-eastern border with Botswana.

It is one of three places in Namibia where flamingos come to rest. From the great lakes of Africa, most famously the sulphur-rich Lake Natron in Kenya, they fly to the Walvis Bay Wetlands, the Etosha Pan and this pan. How they know when there is water is one of the mysteries of nature. (Of course, it is possible the riddle has been solved already, but I still prefer to believe us humans do not need to know why and how, just yet.)

The Nyae Nyae Pan is not along any popular travel route. In fact, it is not a place one would accidentally chance upon. You plan for it. When the universe conspires to make it happen when the season and rainfall is perfect, and when even the moon is full, an Easter long weekend makes the trek to the middle of nowhere a reality.

Our adventure started in the pouring rain as we headed east, then north-east on gravel and eventually, as the light faded, on a slippery red mud track to a farm shed to pitch tents. Since rain and wetness is something Namibians pray for and never, ever detest, even wet firewood and half-cooked chops are a slim price to pay for glorious rainstorms on parched earth. Sliding through muddy puddles on a red clay road is the biggest fun if you have an experienced driver behind the steering wheel of a strong 4×4. At last we arrived at Tsumkwe, the only village near the Khaudum National Park. This area, formerly called Bushmanland, also includes the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, where the San people have the right to hunt.

The wonder of the sight of the thousands of pink flamingos wading in the reflection of clouds is a sight to behold. It is quite a challenge to photograph them because the individual birds constantly move their feet to whirl the mud to release the organisms which they then filter from the water with their beaks. Flamingos can only feed with their heads upside down. Perhaps not the only living creature to do so, but certainly the most spectacular.

These ballerinas of the sky come down to the water to join a variety of ducks, black-winged stilts, marabou storks, spoonbills, Egyptian and spur-winged geese, openbill storks, wattled cranes, herons and the common sandpiper. Not to mention all the regular little beauties on the water’s edge and the surrounding trees.

A body of water always attracts all kinds of activities. Do not expect to see hundreds of springboks with little ones and then catch a glimpse of two cheetahs in the tall grass stalking. But you may just be so lucky.

The amber sky and red sun setting in the dusty haze of winter sky is lovely, but somehow summer sunsets with billowing white clouds turning all shades of pink with a dark gunmetal-tinged eastern sky is magical. To look at this spectacle reflecting in water, is otherworldly.

May you have that treat one day soon.