FINDING TREASURE in the middle of nowhere

Text & Photographs Le Roux van Schalkwyk

From the Winter 2022 issue

What enticed men to leave their homes in Europe for a far-off German colony on the African Continent to dig through burning gravel under the relentless sun of the Namib Desert for a gemstone made of carbon arranged in a crystal structure? Many romantic stories are told citing various reasons, but in actual fact these men were motivated by one thing alone – greed.

That said, these fortune seekers in Lüderitz and the area later known as the Sperrgebiet (German for prohibited area) have gone down in history through a wealth of stories of intense hardship and suffering, successes and losses as well as unimagined wealth and unsustainable opulence. The mad rush that occurred after the discovery of a diamond by railway worker Zacharias Lewala in 1908 left its mark on the desert in the form of vast plains covered in gravel heaps, rows of disintegrating trommel sieves and ghost towns, the most famous of which is Kolmanskop. While Kolmanskop is always worth a visit, seeing the ghost settlements south of Lüderitz holds an almost unexplainable appeal. Maybe it has something to do with the buildings being less disturbed because the Sperrgebiet had been off limits for such a long time. Maybe it is because the desolated areas in which those old settlements are found make you feel as if you were the first person to uncover these archeological gems.

It is weird to think that mining tourism can have so much appeal. Imagine the worked-out remains of Namibia’s grotesque open pit gold mines one day being visited with a sense of romanticised longing for the past and taking photos of disintegrating mining equipment in areas where nature has been completely destroyed. Yet, these mining relics of more than a century ago have considerable tourism value.

The Sperrgebiet was proclaimed the Tsau //Khaeb National Park in 2008. It covers an area of 2,2 million hectares, the majority of which falls within the Succulent Karoo biome. It had been closed to the public for more than a hundred years to protect the diamond wealth of the area. As a result, the fragile Succulent Karoo ecosystem, which boasts the highest diversity of succulent flora globally, was left largely undisturbed for all these years – an amazing feat when considering how rare it is to have a protected area such as this in modern times.

Around 1050 plant species are known to occur in Tsau //Khaeb National Park. That is nearly 25 percent of the entire flora of Namibia on less than three percent of the country’s land area. The Succulent Karoo is listed as one of the world’s top 34 biodiversity hotspots.

For this reason, any form of tourism in the area had to be well thought through as it holds the potential to adversely affect this preserved area. A tourism development plan was drawn up and approved in August 2019 for a period of 10 years. As part of the development plan, nine tourism concessions were awarded by the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism with very strict guidelines.

The concession that covers the mining tourism hot spots as well as the awe-inspiring Bogenfels, was awarded to a company called Sandwich Harbour 4×4, which recently invited the TNN team on its Bogenfels and Diamonds Scenic Tour.

The full-day tour enters the park through the Rotkopf entrance gate some 20 kilometres east of Lüderitz. The first stop, after a short drive, is Grillental. This was an important pump station (water is not easy to come by in the desert) that provided fresh water to the mining towns several kilometres away. Apart from a couple of buildings, tools are scattered through the area, a reminder of the hard labour on this site all those years ago.

Driving further, the route takes guests through a diverse landscape of rocky outcrops, shifting dunes and, of course, the gravel plains that held the promise of the sought-after diamonds. The only remnants of the diamond days are hundreds of gravel heaps that were sifted through for the valuable stones.

Just before reaching the ghost town of Pomona, the tour passes through Idatal, named after August Stauch’s wife. Stauch is famous for starting the diamond rush after Zacharias Lewala, the above-mentioned railway worker under his charge, brought him the first stone. According to Stauch, the valley was so rich in diamonds that when his party discovered Idatal the men crawled on their stomachs at night picking up the stones that glittered in the moonlight.

Pomona with its abandoned houses and their disintegrating wooden frames, is similar to Kolmanskop, but it covers a larger area with a lot more manmade remnants strewn around. The narrow-gauge railway tracks, once the lifeline to the Lüderitz harbour, are only discernible by the rust-coloured lines on the ground. The metal has completely rusted away.

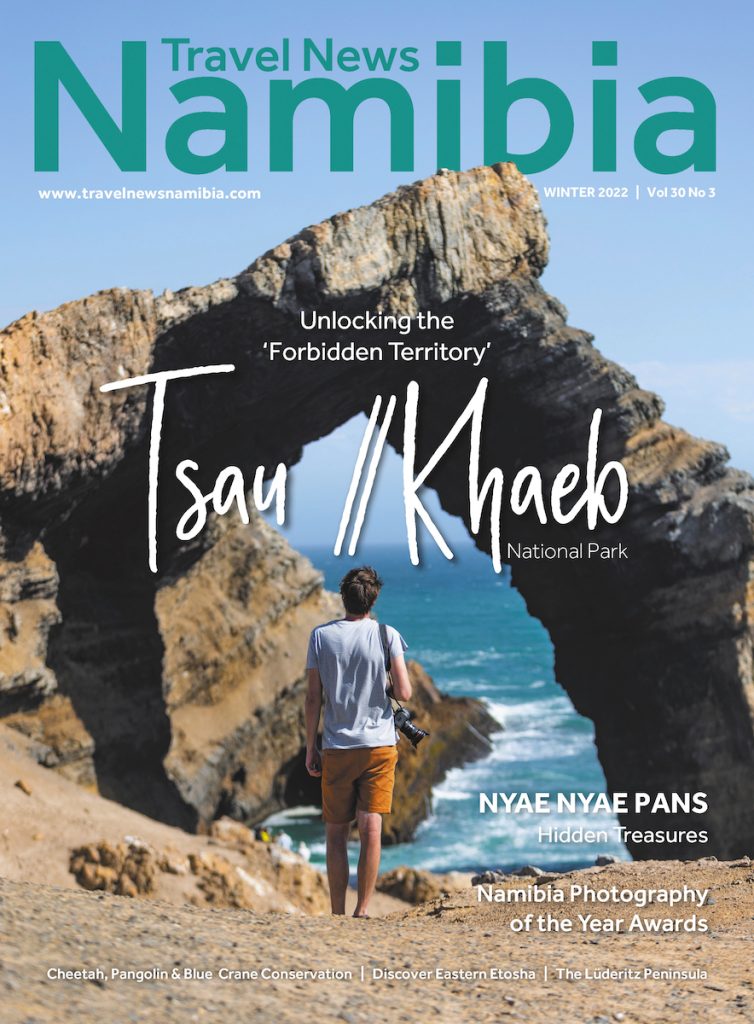

After a delicious lunch, which includes oysters, the tour departs for the natural highlight of the southern coast – Bogenfels. The massive rock arch is 55 metres high and arches over the Atlantic shore. It is a sight to behold and difficult to explain in its striking beauty and size. Barely visible when driving towards it, Bogenfels never fails to impress even returning visitors. A walk to the top of the arch affords amazing, if slightly scary (for those with a fear of heights) views of the surrounding area. While a look at the arch from below offers a completely different perspective of the giant rock structure.

Exploring the remnants of the settlements of the diamond pioneers gives a little insight into what it must have been to battle the elements – heavy fog, wind, sand storms and a burning sun – in a remote part of an unknown country. The former settlements of these adventurous spirits have been preserved by the desert. They allow extraordinarily fascinating glimpses into the past and what some would do for the ultimate prize of a small stone and the promise of wealth.